The Night Digger

The Night Digger (which was known by the more prosaic title of The Road Builder in the UK) was another small British film about a psychotic killer, a genre into which Herrmann seemed to have been strait-jacketed. Based on a novel called Nest in a Falling Tree, it boasted a script by Roald Dahl, the writer of delightfully bizarre stories for children, and Saki-like tales of revenge with a macabre twist for adults. Hitchcock had made one of these (Lamb to the Slaughter) into one of his most celebrated TV shows. In The Night Digger a middle-aged woman (Patricia Neal – Dahl’s wife in real life) becomes infatuated with Billy Jarvis (Nicholas Clay), a young handyman who hides a dark secret.

The Night Digger (which was known by the more prosaic title of The Road Builder in the UK) was another small British film about a psychotic killer, a genre into which Herrmann seemed to have been strait-jacketed. Based on a novel called Nest in a Falling Tree, it boasted a script by Roald Dahl, the writer of delightfully bizarre stories for children, and Saki-like tales of revenge with a macabre twist for adults. Hitchcock had made one of these (Lamb to the Slaughter) into one of his most celebrated TV shows. In The Night Digger a middle-aged woman (Patricia Neal – Dahl’s wife in real life) becomes infatuated with Billy Jarvis (Nicholas Clay), a young handyman who hides a dark secret.

Just as he made an unconventional choice in scoring his previous film with an eerie human whistle, the composer elected to depict the unstable mind of Billy Jarvis through the wheezing sound of a harmonica. Two years earlier John Barry had chosen the same instrument for his plaintive theme for Midnight Cowboy, and John Williams would shortly use it for his first Spielberg picture The Sugarland Express. Rejecting any such folky Mr Bojangles associations, Herrmann made it the sound of another twisted bundle of nerves, and produced one his late great scores.

With its stabbing, churning strings, the music invites comparison with Psycho, but Herrmann also adds a warmer lyrical tone in solo passages for the viola d’amore, the instrument he spotlighted in On Dangerous Ground. Available in the form of a “Scenario Macabre for String Orchestra” on Label X (LXCD1002) and on Bernard Herrmann At The Movies (ATM CD 2003), it’s one of the composers great underrated works.

The Battle of Neretva

The Battle of Neretva was one of those big war movies – like The Longest Day and A Bridge Too Far - that ended up being as big a logistical nightmare as the campaign it was portraying. Shot in 1969 on a state-sponsored budget in what was then Yugoslavia, it included Yul Brynner and Orson Welles among its mostly indigenous Serbo-Croat-speaking cast. Dubbed into English for an international release in 1971, it provided Herrmann with a vast canvas to work on, even though its original three hour running time had been whittled down to 102 minutes. Herrmann, in fact, compared the film to “a great big roast beef”, overdone in parts and undercooked in others. If his music was to be the gravy, then he poured it on thick.

The Battle of Neretva was one of those big war movies – like The Longest Day and A Bridge Too Far - that ended up being as big a logistical nightmare as the campaign it was portraying. Shot in 1969 on a state-sponsored budget in what was then Yugoslavia, it included Yul Brynner and Orson Welles among its mostly indigenous Serbo-Croat-speaking cast. Dubbed into English for an international release in 1971, it provided Herrmann with a vast canvas to work on, even though its original three hour running time had been whittled down to 102 minutes. Herrmann, in fact, compared the film to “a great big roast beef”, overdone in parts and undercooked in others. If his music was to be the gravy, then he poured it on thick.

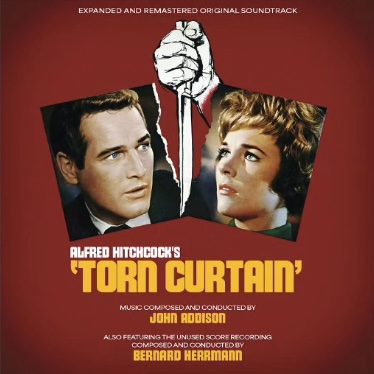

He assembled an army of musicians to play the most bombastic score of his career, a huge fortress of sound that towered over the film. Among the themes he included was the unused murder music from Torn Curtain (it’s not recorded whether Hitchcock ever saw the picture) and a delicate melody from Souvenirs de Voyage, a clarinet quintet he had written for his wife in 1967. It’s unlikely that anybody but Herrmann was aware of these self-borrowings at the time. One of the stand-out tracks is “The Retreat”, which captures the futility of war with a slow deliberate march set against a long yearning melody for strings. I’m listening to that cue right now on the Bernard Herrmann At The Movies disc (Label X ATM CD 2003). The Tribute Film Classics label are bringing out a re-recording of the score in the summer of this year.

Endless Night

Endless Night was a British movie based on an Agatha Christie whodunit set in an isolated house on a stretch of remote English coastline. The film was given a theatrical release in the UK in 1972, but its poor reception led it to being sold directly to American TV. Murder on the Orient Express was still two years away, and producers had not yet twigged to the fact that Agatha Christie adaptations always worked better as period pieces. The Grand Dame of crime fiction did not care for the modern tone of the film and was shocked by the inclusion of nudity.

Endless Night was a British movie based on an Agatha Christie whodunit set in an isolated house on a stretch of remote English coastline. The film was given a theatrical release in the UK in 1972, but its poor reception led it to being sold directly to American TV. Murder on the Orient Express was still two years away, and producers had not yet twigged to the fact that Agatha Christie adaptations always worked better as period pieces. The Grand Dame of crime fiction did not care for the modern tone of the film and was shocked by the inclusion of nudity.

Herrmann was full of enthusiasm when he started work on the picture. Still experimenting with unusual orchestrations, he hit on the idea of using a Moog synthesizer to give the score an eerie quality. In 1968 Walter Carlos had released Switched On Bach, an album of classical music reinterpreted with the Moog, which quickly became one of the highest-selling classical discs of all time. Carlos would go on to work with Stanley Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange and The Shining (he would also become a she – Wendy, like Jack Torrance’s wife – after sex reassignment surgery in 1972). The Moog was an established part of rock recordings and The Beatles had experimented with it on some of the tracks for Abbey Road in 1969. The first film soundtrack to be credited with its use is John Barry’s adrenalin-pumping score for the James Bond movie On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in the same year. Herrmann became so enamoured with the instrument’s possibilities that he used it in his next two scores.

Endless Night, however, proved to be a disappointing experience for Herrmann, and, embarrassed by the final product, he turned down an invitation to attend a screening with the author’s husband. Had the film been a success, Herrmann’s score might not have become the rarity it is today. Unreleased on disc, it can only be heard as it was meant to be, as background to the film on DVD.

Sisters

The Seventies saw the rise of a new breed of film makers – once dubbed the Movie Brats, or, as Billy Wilder called them, “the kids with the beards” – a cine-literate generation who had grown up on movies and TV. They formed the vanguard of a new Hollywood, and, although they initially rejected the old studio system in favour of independent guerrilla-style film making, they were respectful of those that had gone before them. Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, John Milius, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma were starting to make names for themselves, and for a few brief years – before corporate merchandising tempted many of them over to the dark side – Hollywood was an exciting place to be a movie maker.

The Seventies saw the rise of a new breed of film makers – once dubbed the Movie Brats, or, as Billy Wilder called them, “the kids with the beards” – a cine-literate generation who had grown up on movies and TV. They formed the vanguard of a new Hollywood, and, although they initially rejected the old studio system in favour of independent guerrilla-style film making, they were respectful of those that had gone before them. Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, John Milius, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma were starting to make names for themselves, and for a few brief years – before corporate merchandising tempted many of them over to the dark side – Hollywood was an exciting place to be a movie maker.

If George Lucas took his inspiration from the Hollywood serials, Spielberg couldn’t decide whether he wanted to be John Ford or Frank Capra. John Milius was either the new Howard Hawks or Sam Fuller. Scorsese – with his encyclopedic knowledge of American cinema – was happy to reference just about everybody from D.W.Griffith to Douglas Sirk. Out of them all, perhaps only Francis Ford Coppola was his own man, in thrall to no discernible influence (with the exception of Antonioni for The Conversation). Brian De Palma, of course, wanted only one thing: to be the new Hitchcock. He would, in fact, make a small career out of an almost obsessive imitation of some of the director’s great works: Obsession for Vertigo, Dressed To Kill for Psycho, Body Double for Rear Window. The film that set him on this path was Sisters, and what better way to pay homage to Hitchcock than use Hitchcock’s composer?

Actually, it was the editor Paul Hirsch, who had used the music from Psycho as a temp track while cutting the film, who convinced De Palma that Herrmann was their man. The initial meeting when they screened their rough cut for the composer was not auspicious. They had left some of the temp scoring on the soundtrack and, when the Marnie theme filled the screening room, Herrmann flew into a rage. He finally calmed down only to blow his top again when De Palma and Hirsch explained that there was to be no title music. “I will write you one title cue,” Herrmann told them. “One minute and twenty seconds long. It will keep [the audience] in their seats until your murder scene. I got an idea using two Moog synthesizers.” Herrmann was on board.

The music he wrote to accompany the main title images of a pair of demonic looking foetuses delivered on his promise – nothing else in the entire movie lives up to its raw savagery. The score oscillates between a swirling cacophony of wailing Moog, blaring borns and shrieking strings and quieter – but no less chilling – interludes of childlike melodies on the glockenspiel.

The soundtrack is available on the Southern Cross label (B000056WOD). One of the cues is also available on the Ghosts of Bernard Herrmann (ILL 313002), a compilation of the composer’s greatest hits arranged for solo piano – a curio of an album, but highly recommended.

It’s Alive

It’s Alive was the story of a killer baby that goes on a murderous rampage in the delivery room, terrorises Los Angeles, and ends up – like the ants in Them! – cornered by the military in the city’s storm drains. The film no doubt spoke to the same anxieties of parenthood that Polanski had drawn upon for Rosemary’s Baby and which were to inform the cycle of demon-child movies that began with The Exorcist and The Omen. Exploitation director Larry Cohen’s movie had none of the style or sophistication of those big-budget studio pictures. Yet for all its schlock-horror schtick, it has one thing going for it that lifts it above its Z-movie origins: the scorching performance of John P. Ryan as the bewildered father of the monstrous baby.

It’s Alive was the story of a killer baby that goes on a murderous rampage in the delivery room, terrorises Los Angeles, and ends up – like the ants in Them! – cornered by the military in the city’s storm drains. The film no doubt spoke to the same anxieties of parenthood that Polanski had drawn upon for Rosemary’s Baby and which were to inform the cycle of demon-child movies that began with The Exorcist and The Omen. Exploitation director Larry Cohen’s movie had none of the style or sophistication of those big-budget studio pictures. Yet for all its schlock-horror schtick, it has one thing going for it that lifts it above its Z-movie origins: the scorching performance of John P. Ryan as the bewildered father of the monstrous baby.

Unfortunately, Herrmann’s score is a mess: overcooked, over-the-top and all over the place. What a tragedy it would have been if this had been the score that had closed his career. And who could have guessed, based on the evidence of It’s Alive, that he would go on to produce two of his greatest works within a year? For completists, a version of It’s Alive is available on It’s Alive 2 on the Silva Screen label (B000003QQ8). The music for the sequel is basically a rehash of the original themes, cobbled together by the composer’s friend Laurie Johnson.

Obsession

Obsession was another Brian De Palma exercise in Hitchockian ventriloquism. With Vertigo withdrawn from circulation and not to resurface until the mid Eighties, De Palma could make a carbon copy of its dead-woman-replaced-by-lookalike-by-obsessed-grieving-lover storyline with impunity. De Palma couldn’t resist putting a further twist to the tale by adding an Oedipus Complex to an already preposterously complex plot.

Obsession was another Brian De Palma exercise in Hitchockian ventriloquism. With Vertigo withdrawn from circulation and not to resurface until the mid Eighties, De Palma could make a carbon copy of its dead-woman-replaced-by-lookalike-by-obsessed-grieving-lover storyline with impunity. De Palma couldn’t resist putting a further twist to the tale by adding an Oedipus Complex to an already preposterously complex plot.

When Michael Courtland’s (Cliff Robertson) wife and young daughter are abducted, he involves the police against the kidnapper’s instructions and, in a bungled ransom drop, his family are killed. Years pass and, still a grieving widower, Courtland visits Florence on a business trip. Here he meets Sandra (Genevive Bujold), a young woman who bears an uncanny resemblance to his dead wife. As Courtland begins to court her, he tries to turn her into a replica of his late wife. The two eventually marry but on their wedding night Sandra is kidnapped. In a dramatic re-enactment of the original ransom drop – with Herrmann’s music driving the action and providing the emotion – Courtland learns that his business partner is behind the whole thing, and that Sandra is his long lost daughter. The final shot of the movie – a dizzying 360 degree camera movement that increases speed with each revolution – shows father and daughter locked in an incestuous embrace.

For this overripe melodrama Herrmann composed a score of ravishing beauty with a sonorous church organ providing its emotional core. The composer had suggested using just such an instrument to William Friedkin when he was asked to write the score for The Exorcist, and, at the time of his death, he was sketching out an organ symphony. Herrmann contributed more than just the music. He devised the title sequence, outlining it frame by frame to the director so that it would dovetail perfectly with his haunting “Main Title”. The writing of this most spiritual of his scores seemed to have had a cathartic effect on the composer and he gave way to his emotions, breaking down in tears when the actress Genevieve Bujold thanked him for his contribution. Or maybe, he was simply tired. Just five months away from death in a Hollywood hotel, he found the recording sessions in St Giles Church in Cripplegate in London an exhausting experience, and, just as he had with his Psycho re-recording, asked his friend Laurie Johnson to take over the conducting for the final long cue.

Herrmann did not live to see the release of the movie. It came out in the summer of 1976 to appreciative reviews and a respectable box office take. Along with Taxi Driver, it was nominated for an Academy Award. It didn’t win, but it didn’t matter. For Herrmann the composition of the work had been its own reward. the soundtrack was released at the same time as the movie (B003QMZ3JM). I have the incomplete version on the Welles Raises Kane Unicorn disc (UKCD2065), which I’m listening to right now. It suffers from some savage editing and sudden transitions, but it’s still a sublime piece of work.

Taxi Driver

Martin Scorsese had a hard time convincing Herrmann to write the score for Taxi Driver. He first pitched the idea to him over the phone from Amsterdam, but the composer wasn’t interested. “Oh no,” he said, “I don’t do things about cab drivers. No, no, no.” The director wasn’t about to give up: American cinema was part of his DNA, and within that DNA there were strands of Herrmann, spiralling from the great Hitchcock scores of the Fifties right back to the ominous brooding opening of Citizen Kane. Scorsese wanted his film to be “New York gothic” and he knew that Herrmann’s “poetic morbidities” would be a perfect fit for the images that he had in his head. The director suggested a meeting, but the composer rebuffed him. Their dialogue went back and forth, each time ending with another refusal. When the two men finally met in London, Herrmann had read the script that had been sent to him. At last when he agreed to do the picture, Scorsese was curious as to what had finally convinced him. “I liked when he poured peach brandy on the cornflakes,” Herrmann replied. “I’ll do it.”

Martin Scorsese had a hard time convincing Herrmann to write the score for Taxi Driver. He first pitched the idea to him over the phone from Amsterdam, but the composer wasn’t interested. “Oh no,” he said, “I don’t do things about cab drivers. No, no, no.” The director wasn’t about to give up: American cinema was part of his DNA, and within that DNA there were strands of Herrmann, spiralling from the great Hitchcock scores of the Fifties right back to the ominous brooding opening of Citizen Kane. Scorsese wanted his film to be “New York gothic” and he knew that Herrmann’s “poetic morbidities” would be a perfect fit for the images that he had in his head. The director suggested a meeting, but the composer rebuffed him. Their dialogue went back and forth, each time ending with another refusal. When the two men finally met in London, Herrmann had read the script that had been sent to him. At last when he agreed to do the picture, Scorsese was curious as to what had finally convinced him. “I liked when he poured peach brandy on the cornflakes,” Herrmann replied. “I’ll do it.”

His ideas for the score quickly coalesced and he had the music mapped out in the mind even before he had seen a frame of the film. Like the film’s main character Travis Bickle, the score has a schizophrenic quality (as, indeed, would the original soundtrack Arista album). There was the lush jazz motif, suggesting the beauty of the blurred neon reflected in the rain-washed streets, a rich saxophone refrain that provided a deceptive romanticism of urban life. It’s the kind of music you expect to accompany a private detective as he walks down the mean streets of the city – in fact, like the theme David Shire wrote for Farewell, My Lovely in the same year. In contrast, there were the strident chords of brass, the ticking bass and the relentless percussion that suggested the coiled anger of the main character just waiting to explode. Those who criticise the Taxi Diver score for being uneven are missing the point – its fractured beauty, the cracks and faultlines that scar its glassy surface, these are an integral part of the composer’s concept.

The music serves the film well, but perhaps is less satisfying to listen to on disc. The original soundtrack release (Arista 258774) contained little of Herrmann’s original score. One side of the vinyl was dedicated to “interpretations” of the music arranged and conducted by Dave Blume. These were beautifully played jazz numbers, but – with the exception of the instantly recognisable “Theme from Taxi Driver” – they seemed to have little to do with the movie. Side Two of the record opened with one of Travis Bickle’s monologue (cleverly edited to erase the profanity) with Herrmann’s score providing a quietly menacing backdrop. There were then just four tracks of Herrmann’s original score to round out the disc. A remastered complete soundtrack (07822-19005-2) came out in 1998.

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](../../../wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](../../../wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](../../../wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](../../../wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](../../../wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)