Moores was born in 1941 in New Zealand and went later to the UK. After studies in the US he returned to London in 1971 where he started to work for John Goldsmith who formed the Unicorn label and this introduced Mr. Moores to a certain American composer…

I took a job at a record shop. And the shop turned out to be the “Record Hunter”, which was a small specialist shop … at the South Bank at Waterloo … that had been run by John Goldsmith, who founded the Unicorn label. And I just thought of it as a temporary job, but the more I got into the work, the more I enjoyed it!

It was a labour of love, because I love music and collected records. I spent a lot of time (4 years) in America and I collected records there…

So I took his specialist side and redeveloped it again. I learned all the time from customers and so during the 70′s I became more and more interested in unusual repertoire… and around that time Bennie Herrmann started to sponsor recordings on Unicorn [as he had done] a little earlier on Pye. Unicorn had the same kind of enthusiasm for his music that I did…

A happy conjunction, really. And I got to meet him through John Goldsmith at Unicorn. And as John realised my enthusiasm for Bennie’s music we began to organise some occasions at the record shop that I was managing.

It wasn’t the “Record Hunter” by that point anymore. I moved on as I was offered the job of reorganising and managing quite a famous old firm called “Henry Stave” in Dean Street. That has been going since the early 50ies one of the old-time record shops.

This is really where my friendship started with him. When he started to come the shop, almost once a week, we would go and have lunch together. And I was quite flattered that somebody who to me was a famous composer should take an interest in me. And he in turn, I guess, was keen that someone in a younger generation, as I then was, … would carry on his reputation. He was concerned about posterity’s interest in his music… So we had this series of regular meetings.

But he was clearly not a well man. I’d say in fact he was quite ill. And there was one particular occasion when he came to the shop, when he really was quite ill … [we] went out … and tried to help him in his difficulties, and I don’t think he ever forget that. There was a sort of sentimental attachment… For a time, I think, he regarded me as a substitute son…

We talked a great deal about music, composers, performers, conductors. And in his own unique irascible way we had some good disagreements, but I didn’t find him frightening. I think I saw through him straightaway … That he had this very gruff New York exterior. I mean New York is another country, and he was from that separate country: New York! … when you climb on a bus in New York you get the flavour. Everybody around you the got this sort of tough, irascible style – and he had that down to a tee!

And it was born not only out of his background, but also his frustration with the film industry and what they were looking for and what he didn’t want to give to them at times. He gave them an enormous amount, but… … I saw through him straightaway really. I saw that he had the tenderest of hearts. And he was particularly solicitous… My wife at the time was having her first child and he used to literally call me every day to find out how she was. She had to go into hospital early. With all that I could see through him really. Beneath the crusty exterior there was a very tender heart. It comes out in many passages in his music… “Wuthering Heights” and many of the film sequences where you suddenly get that really wistful, tender music.

So, I think we understood each other. Not to say that I always agreed with his views. I remember him being particularly, I think you have to use the word, vicious, about a particular conductor…

What most impressed me was his breath of knowledge of other composers, especially late 19th Century and early 20th Century French and European composers. And indeed of course British composers, he had a particularly soft spot there.

He had a fantastic knowledge of obscure repertoire. Later I realised how much he conducted for the CBS Symphony…

Knowledge of that sort of repertoire was put to good use in Citizen Kane in that wonderful make-believe French aria. A glorious piece of music!

Rediffusion turned down Kiri Te Kanawa before she was signed up to anyone. To that point the [Gerhardt] RCA record… That was the first thing. She went on being involved in some of the opera series in supporting roles in Carmen and so on… But hadn’t made a solo record with that one exception of that one aria in the Citizen Kane album!

I went to one or two recording sessions at Kingsway Hall … He was visibly slowing down at all those. I mean literally slowing down in his conducting… and I remember disagreeing with him about the tempi, very presumptuous of me, for the Shostakovich Hamlet that he did, which I felt was too slow. And I loved the film and loved the music and had enormous enthusiasm for Shostakovich’s film music. And I always felt that this was too slow.

The session that I went to was worked up by Charles Gerhardt… and he was an important figure in all of this at that point. Not only for his own fine efforts for the RCA series, but the session I went to, he was very much involved in preparing everything and Bennie sort of took over. But I think, Bennie inclined to slow things a bit.

I remember a long car journey with him… I took my wife, Norma and Bennie up to somewhere in the northern part of the midlands… Nottinghamshire or even further, where John Goldsmith has bought a house… we had some *long* conversations going on in the car!

Norma was solicitous and she looked after him… But it must have been very difficult for her… This may be presumptuous of me to say all this … but he’d been a late middle aged man when they got married… who within short time really turned into an elderly man through heart attacks and general decline. So there she was married to an elderly sick man; that must have had its own strains. But I wasn’t aware of them…

I can still remember sitting in the cinema and seeing the Saul Bass titles for the first time, about 1959 I would think…

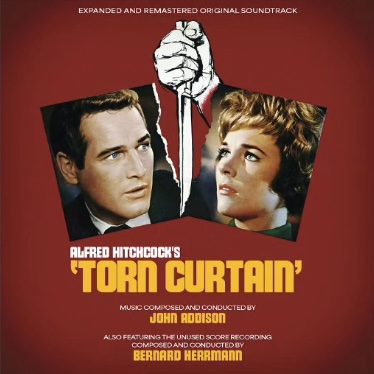

I still love [Vertigo] very much and I particularly like the music in that film. And I do strongly hold the view that Hitchcock’s films were greatly reduced without Herrmann’s music. Take away the music and it reduces them considerably. I always think about them as Hitchcock/Herrmann films because the contribution is so important…

And so I rapidly found that I loved so much, almost all of his music, and I set about acquiring and listening to anything I could find and I do still feel the same way. I collect the music of Janacek and Bernard Herrmann…

There are now problems with the Unicorn catalogue. A lot of the Unicorn recordings are disappearing now… the company might even be closed. I am not sure. So many of these might start to disappear now. Some of the things we are trying to order haven’t been coming. The Herrmann and Horenstein titles will be the first to disappear, there is an ongoing demand.

He did show some regrets [about being a composer for films], he wanted to spent more time composing for himself, you might say, rather than films. But film was obviously a great stimulus for him.

He was a formidable man… uncompromising in his standards… Nothing second rate, it had to be the best and that’s the standard he demanded of people he worked with in filmmaking… He respected quality. No problem if somebody was doing something of quality, no problem at all.

At some times he was less “charitable” than he ought to be about people he knew about by reputation, but he really didn’t know… The business about the conductors… Solti and Mehta… you could criticise certain aspects of their style, but they made wonderful recordings. They were/are hardworking people… but he picked up on a sort of public image… I suppose a little bit of jealousy there…

But his is going to be an enduring reputation…

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](../../wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](../../wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](../../wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](../../wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](../../wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)